While researching the life and work of painter Robert Bateman, a concealed ‘work of art’ was discovered in the woodland adjoining Biddulph Old Hall – the little mill stream in the steep wooded valley below the house had been manipulated by the building of two dams to hold the water back into ponds or small lakes, and the rock had been blasted to create a continuous series of waterfalls, rapids and flat rock plains.

During the century since Bateman’s death almost all trace of this dynamic water garden has been lost through neglect, mutilation and vandalism. Both dams have been destroyed, one by being breached by a concrete pipe, the other by being blown up in the 1980s. Trailer loads of debris have been tipped from the top of the valley, turning the fetid swamps where the lakes had been into rubbish dumps of half submerged corrugated iron, tractor tyres and rusting supermarket trolleys. Despite the dereliction, the valley retained an uncanny, hypnotic appeal, an intense aura of secrecy or privacy. Owner Nigel Daly described it in his book on Bateman as:

“The mournful ghost of a beautiful place, disfigured but still faintly discernible.”

Maps and written sources from the 19th century later confirmed his initial intuition about this numinous place.

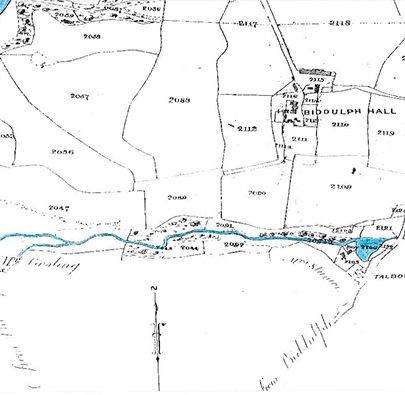

The original line of the Clough stream in 1862.

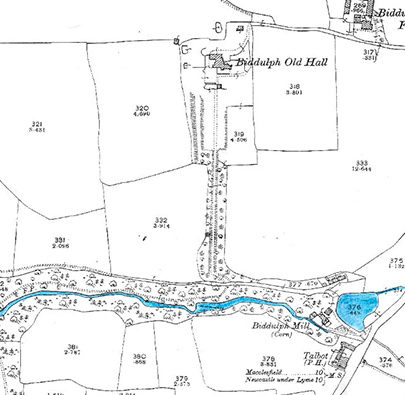

An extract from the 1899 OS map showing the two dams and the line of the walk from Biddulph Grange through the Clough up to Biddulph Old Hall.

Biddulph Old Hall is a mere ¾ of a mile from Biddulph Grange, the Victorian mansion built by Robert Bateman’s father, the famous horticulturalist James Bateman in 1842. The gardens he created at The Grange are arguably the most botanically important and artistically flamboyant example of mid-Victorian taste anywhere in the country, which in the 1980s were acquired by the National Trust and fully restored. Records show that in 1861 James Bateman bought the Elizabethan ruins of Biddulph Old Hall as the ultimate garden folly, and connected it to the Grange garden by the ¾ mile walk beside the Clough stream in the wood. It was an ambitious project involving the building of several bridges, two dams, tunnelling under a road and the construction of many flights of steps.

James Bateman left for London in 1868, and sold the whole Biddulph Grange estate in 1871; hence the water garden represents the final creative flourish before he was forced to abandon his horticultural wonderland through a shortage of money. Although Biddulph Old Hall and the Clough stream were sold with the estate, James arranged for a lifetime tenancy for his third son Robert, who retained the right to both until his death in 1922.

Robert Bateman with his wife and a friend on one of the bridges in the Clough in the mid 1880’s.

A view of the Clough stream with steps and visitors in the 1890’s

Robert was a leading member of the so-called ‘Dudley Group’ of artists – second generation Pre-Raphaelites and followers of Burne-Jones. The group were vividly summed up by Walter Crane, a friend of Robert’s, as being preoccupied with:

“a magic world of romance and pictured poetry, peopled with ghosts of ladies and lovely knights – a twilight world of dark mysterious woodlands, haunted streams, meads of deep green starred with burning flowers, veiled in a dim and mystic light.”

Although this gives no indication of the range and skill of Robert Bateman’s work, it does offer a clue to his continuing fascination with, and development of, a Pre-Raphaelite landscape around his ruined castle. Between 1873 and 1890 he had left London and abandoned the Dudley Gallery. During these years he lived reclusively at Biddulph and did his most acclaimed work. He seems to have continued to develop the water garden in the Clough, as by 1887 a local writer and historian was sufficiently beguiled by it to describe it as:

“….a very paradise of woodland scenery. Known as the Clough, a gentle ravine circles the lower grounds of the old Castle. Here artistic effect has aided nature in creating one of the prettiest retreats it is possible to conceive. Trickling down from fragments of shelving rock and forming miniature cascades and shadowy basins the whole length of the Clough is a little stream which gradually widens in its fall. Overhanging trees lap their branches in one almost continuous arbour; lichens and mosses grow in luxuriant profusion; and in summer the whole wealth of Fern-land puts forth its beauty to complete a picture worthy of the Dargle itself. Strangers usually visit the ruins, and, oblivious of its existence, pass on without a glimpse of the Clough; but of late years artists have discovered its hidden retreat, and now brush and canvas and photographic art combine to make its romantic beauty more famous and widely known…..”

The waterfall from the upper lake after being cleared.

Two flights of stone steps, both shown in late 19th century photographs and which confirm the route of the walk, have so far been rediscovered and excavated; but the rescue and restoration of the rest of the valley and the water garden are vitally important for two reasons: